Finding meaning in an unfinished portrait of a mother

on absence in art and the politics of care

My friend

recently visited Chicago with her family, and I had the pleasure of taking her and her daughter to the Art Institute of Chicago. The museum is massive, and we only had a few hours, so we moved relatively quickly through the galleries, stopping only to linger when something really stood out.One piece that drew me in was a simple, muted oil painting of a woman. The portrait, located in the Paintings and Sculpture of Europe gallery, is about 5 feet tall and appears incomplete, especially compared to the other, more muralistic Neoclassical works in the room.

The subject in the image has fair skin and loose, sandy-brown curls, half-pinned up, the rest gently falling over her shoulders. She’s seated in a wooden chair, centered in the frame, her body turned slightly to the left toward a natural light source, while her face and gaze are directed outward, meeting the viewer.

In one hand, she holds the end of a strip of white fabric, part of a larger piece that’s draped softly across her chest and shoulder. Her other hand is pinched as if holding a needle, but it's empty. Her dress, made of the same soft white fabric, features a low neckline that reveals much of her chest. It’s cinched tightly at the waist with a light blue sash, and the long, layered skirt spills over her legs to the floor.

Beside her, in shadow, an infant lies in a small wooden cradle, resting its head on a white pillow. He’s so close it’s almost as if he’s bundled in her skirt. The child’s tuft of hair and the faintest suggestion of a profile are so thinly painted that the wood grain from the mother’s chair is visible through it.

The painting is Madame de Pastoret and Her Son, painted in 1791–92 by the artist Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Reading the description, I discovered that the painting is, in fact, unfinished.

Here’s what the placard reads:

The volatile events of the early years of the French Revolution make it impossible to determine with certainty the date of Jacques-Louis David’s warm, fresh portrait of Adélaïde de Pastoret. They also probably account for the portrait’s unfinished state. David, a renowned Neoclassical painter, was at the time an ardent revolutionary; Madame de Pastoret was the wife of a staunch royalist. The sittings must have occurred after the birth, early in 1791, of her son, who is portrayed asleep by her side, and before her brief imprisonment during the Reign of Terror in 1792. Here David completed the stippled, almost monochromatic underpainting but did not create the stark, enamel-smooth surface that is characteristic of his finished paintings. He did not even get far enough to place a needle and thread in Madame de Pastoret’s hand. Nevertheless, this large portrait of unaffected domesticity captures the youthful mother with charm as well as dignity and displays David’s skill as a portraitist. Objecting to David’s revolutionary ideals, Madame de Pastoret (who became the Marquise de Pastoret in 1817) refused the painting during the artist’s lifetime. After David’s death, she had her son, by then an adult, purchase the portrait from the artist’s estate.

My reflex was to judge her, separating myself from her. Through a lens of good and evil, I was good. Smugly, I thought, “Unlike her, I’d choose art over kings.” I stood back and looked again, paying special attention to what was present and what was missing.

It’s a stunning painting by a skilled artist—a portrait of motherhood and domesticity with the baby, the needle, and the thread missing.

The painting stuck with me, and later, I found myself digging into the artist and subject.

I discovered she was a royalist and a philanthropist, particularly in her support for women and children. I read one account that claimed she was inspired to establish a chain of nurseries for the children of working mothers after a chance encounter with an injured baby and the five-year-old left in charge of caring for him while his mother was away. She supported mothers, children, and public health, and likely shaped how she was portrayed in the piece: as nurturing, dignified, and maternal. I did not find any other renderings of her.

Here’s one of her husband, Claude-Emmanuel de Pastoret, a mostly anti-slavery/pro-monarchy moderate, painted by Paul Delaroche.

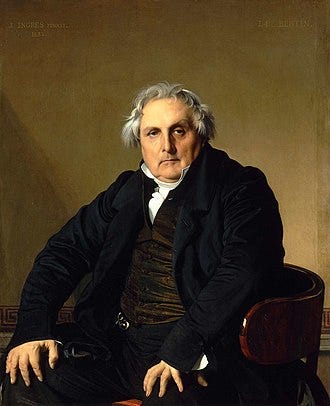

And here are two paintings of the baby, Amédée-David de Pastoret, as an adult. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres first painted him at age 32 and again at 66. Amédée-David grew up to become even more conservative than his parents. He was a devoted supporter of aristocratic power structures, once described as “a social climbing sycophant, beset by excessive pretension”(aka a total asshole).

A fuller story complicates the image of mother and child. Despite her care-focused efforts, Madame de Pastoret and her husband aligned with political structures that preserved inequity. They accepted that society had room for improvement. She supported women—but within a system that forced others into poverty and overwork. Her care was conditional, restricted by class and allegiance.

As a royalist, she supported social structures that gave power to the wealthiest at the expense of the vast majority. As a member of a protected class, she opposed the radical, revolutionary changes that aimed to create a more democratic and equitable society. In her home, she played the role of mother. Even in her community, she worked to make care more accessible. But structurally, she opposed it.

The more I read about the painting, the more questions emerged. Was she really the one who rejected the painting, or was it her husband? Was she flattened by history, like so many women before and after her? Was the rift with David personal or political? Both? I don’t know, and I’m not a historian. But eventually I landed on the question that mattered most to me: Do the details of what she believed matter if her actions reinforced harm?

She didn’t rock the boat, even when she knew how badly it needed rocking.

There’s something poetic(ironic, really) about a woman who wanted to be remembered as nurturing, cutting ties with the artist who championed care for all. Her portrait, left unfinished, echoes the limits of selective caregiving.

What did this mother believe would be preserved by protecting her comfort while others suffered? What was so threatening about a world where every child, like hers, had clean clothes and a warm bed? She knew the value of care. But extending that care beyond her class was a bridge too far. The unfinished painting is the consequence of that dissonance.

I can’t help but see the parallels today. Right now, the wealth gap in the U.S. is as bad, if not worse, than it was before the French Revolution (when this painting was started). Most people struggle to access healthcare, housing, and childcare. Jobs are scarce while corporate profits boom. Fascism isn’t just on the doorstep. It’s sitting on the couch, feet up on the coffee table.

And still, for many who claim to uphold family values and care, true collective safety is unacceptable. This version of caregiving is exclusionary—giving more to some and less to others—and is, at its core, neglectful and abusive.

That’s the tragedy of this portrait. It’s of a mother who wanted to be seen as nurturing, but refused solidarity. Her care had limits. Her thread never passed through the needle. The unfinished painting is an accidental monument to individualism.

Though it was my initial reaction to do so, villainizing her is an easy out.

The reality is murkier. If she were alive today, she would probably consider herself a feminist. She might head a nonprofit for women in leadership—while staying silent on injustice abroad or at home. She might be “socially liberal, fiscally conservative.” She might “love the sinner, hate the sin”. I might have known her. In some ways, as uncomfortable as it is to admit, I am her.

It feels good to see yourself as morally superior to others. That’s part of why so many of us enjoy reality TV—we’d never make those choices in the same position, right? But if we actually want to be better and not just feel better, we have to sit with the discomfort, not just of how we’re different, but of how we’re the same.

I have a different read on the work than I did at first. I see her shortcomings and the irony of her abandonment of the cause. But with its absent needle and thread, the painting also holds up a mirror to my own shortcomings. Like Madame de Pastoret, I see myself as a caregiver. I want to be seen that way. And, like her, I have limits.

I wonder at what point I would abandon the painting? It invites me to look closer, to question my allegiances. Where does my solidarity end? Who am I leaving behind in my daily life? Which connections am I missing? In what ways is my mending empty and my support thin?

We don’t know the whole story behind the painting. But we know it was started and never finished.

To me, the piece and all its context speak to the politics of care. To the tension between the personal and the collective. To the limits we set on empathy. The missing needle and thread represent solidarity. Without them, she had nothing to connect—no way to bind herself to the world. The portrait challenges us to wonder if we can really claim to be acting in care if that care doesn’t extend past our doorsteps.

All children are our children—locally, globally. There is a thread that ties us together: revolutionary love. Radical care, right down to the roots. It’s our job to notice it, pass it through the needle, and stitch a future where we are all held.

I read this on the podcast this week. You can check it (and my terrible French) here!

also, Laura...read this yesterday and thought of us all: https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/plath/article/view/33214

love this convergence of your substack & history & art 🎨